14th January 2026

Takeaways

Predicting financial market stress remains an elusive task. Traditional econometric models often fail to capture complex and nonlinear dynamics. This article highlights two recent advances in the use of Machine Learning tools to anticipate financial market stress. The first one uses random forest techniques to forecast the full distribution of future conditions in key US markets and explain the main factors driving predictions. The second one combines a recurrent neural network (RNN) and a large language model to forecast disfunction on foreign exchange markets. Both approaches show promise in aiding policymakers monitor emerging risks in real time, and providing them with interpretable, actionable insights.

Introduction

Predicting financial market stress has long proven to be an elusive goal. Such episodes often originate in seemingly isolated segments of the financial system before propagating more broadly through interconnected intermediaries, evaporation of liquidity and broad-based deleveraging.1

Despite advances in econometric modelling, anticipating episodes of market dysfunction remains extraordinarily challenging. For one, traditional econometric models often fail to capture the complex, nonlinear dynamics and interconnectedness of modern financial systems. For another, the infrequency of severe stress events limits the training data available for statistical models, while the unique and often nonlinear transmission mechanisms across markets through which risks materialise make it difficult to identify common patterns across different crisis episodes. Consequently, traditional early warning monitoring approaches have shown mixed success, often suffering from high false positive rates or failing to capture novel sources of systemic risk build-up (Alessi and Detken (2011)).

Recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI) provide new tools to address these challenges. AI methods excel at analysing high-dimensional datasets and uncovering hidden patterns that may escape traditional econometric approaches. They have been applied in asset pricing (Kelly et al. 2024), and are increasingly used for financial stability monitoring (Fouliard et al. 2021, du Plessis and Fritsche 2025). However, the 'black box' nature of AI models has limited their ability to generate actionable policy insights, as policymakers need to understand not just what the model predicts but why.

This note provides a synthesis of recent research by BIS economists (Aldasoro et al. 2025, Aquilina et al. 2025) that advances the deployment of AI tools to anticipate financial market stress. These studies demonstrate the potential of AI tools to anticipate market stress and dysfunction, offering both methodological innovations and actionable insights for policymakers by addressing the black-box issue through interpretability techniques.

Predicting financial market disfunction is challenging

Financial market stress can manifest in different ways, including liquidity shortages, price dislocations, and breakdowns in arbitrage relationships. Events such as the 1998 LTCM crisis, the 2008-09 global crisis, and the 2020 'dash for cash' highlight the systemic risks posed by market dysfunction. These disruptions often begin in specific market segments, such as foreign exchange or money markets, but can quickly spread throughout the financial system, threatening its stability. Increasingly, stress has also shifted from traditional banks to non-bank financial intermediaries, reflecting the evolving nature of financial intermediation and the growing importance of market-based finance (Aramonte et al (2021)).

Several types of market frictions have been incorporated in new generation asset pricing theories, with intermediaries at their heart. As the expansion of balance sheets is costly, following shocks market distortions and fully-fledged dislocations may emerge and not be fully arbitraged away. Research shows that these dislocations significantly increase in proximity to financial stress episodes. One reason behind such mispricing can be the deterioration of market liquidity, which is in itself indicative of markets not functioning efficiently. In some instances, the trading process can completely break down, leading to 'liquidity black holes' where the trading process becomes destabilising rather than stabilising.

In this context, it is crucial to consider feedback mechanisms and the endogenous nature of risk and liquidity (Shin, 2019), which are further amplified by the high degree of interconnectedness across markets through the balance sheets of intermediaries. Periods of apparent calm and low volatility often lead to investor overextension, inadvertently planting the seeds for future market stress. Additionally, key markets are tightly linked through systemically important intermediaries, whose operations span multiple markets and facilitate access to leverage for other market participants.

Traditional early warning systems, which were primarily designed to predict full-blown crises, have had mixed success. These models often suffer from high false positive rates and struggle to account for the nonlinear interactions and feedback loops that amplify shocks during periods of stress. The interaction of funding liquidity and market liquidity can yield downward liquidity spirals, and lack of liquidity may be the precursor to episodes of dysfunction down the road.

Machine learning (ML) offers a promising alternative, particularly for generating early warning signals. Unlike traditional models, ML algorithms can process vast datasets, identify complex relationships, and adapt to changing market conditions. The numerical flexibility of these models enables analyses in high-dimensional settings, which in finance can be particularly advantageous.

Using machine learning to predict tail risks to financial market conditions

Aldasoro et al. (2025) present a novel framework for predicting financial market stress using machine learning. The study first constructs market condition indicators (MCIs) for three key US markets: Treasury, foreign exchange, and money markets. Unlike traditional financial stress indices that often conflate broad sentiment shifts with structural vulnerabilities, the MCIs emphasise market dislocations as reflected in episodes of illiquidity and deviations from no-arbitrage conditions that reflect the balance sheet constraints of intermediaries and the impairment of arbitrage.

The construction of the MCIs involves a two-step process. First, market-specific variables are curated that proxy for volatility, illiquidity, and arbitrage breakdowns. For FX markets, these include the cross-currency basis (the difference between the interest paid to borrow one currency by swapping it against another and the cost of directly borrowing this currency in the cash market), violations of the law of one price in currency triplets, bid-ask spreads, and JPMorgan's FX volatility index. For Treasury markets, the indicators include time-to-quote measures from a major bond trading platform, quoted spreads for securities of various maturities, deviations of observed bond yields from a fitted smooth yield curve, interest rate swap spreads and the MOVE index. For money markets, spreads between repo and OIS rates, commercial paper spreads, and the TED spread are used.

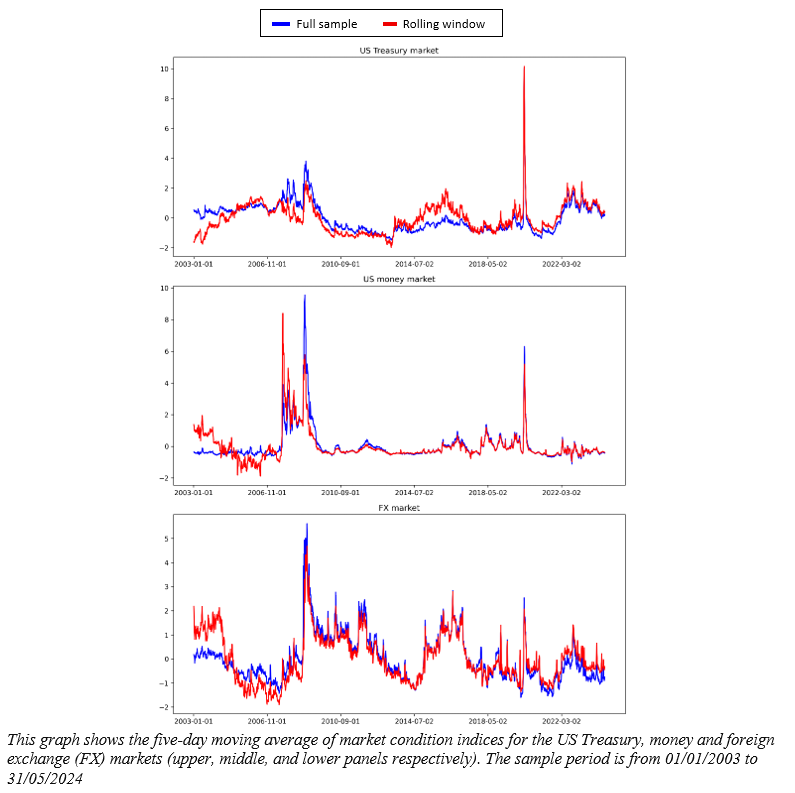

These variables are standardised and aggregated via rolling-window principal component analysis, yielding daily real-time indices normalised to zero mean and unit variance, where positive values signal tighter-than-average market conditions. This out-of-sample approach uses only past information to avoid look-ahead bias.

The MCIs capture well-known stress episodes across markets (Graph 1). For instance, the FX MCI spikes during the 2011-2012 European debt crisis, the 2015 de-pegging of the Swiss franc, and the 2016 Brexit referendum and US money market fund reform. The Treasury MCI reflects deteriorating liquidity during the post-2013 taper tantrum, idiosyncratic flash events in 2014 and 2021, and the 2020 pandemic. Importantly, the MCIs provide complementary information to the VIX, as seen in 2015-2016 when FX stress surged without a corresponding equity volatility spike. This granularity addresses a key limitation of traditional financial stress indices, which often over-rely on equity-derived signals.

The paper employs random forest models, a tree-based machine learning algorithm, to forecast the full distribution of future market conditions using quantile regressions. This approach uses multiple decision trees and averages their predictions, reducing the risk of overfitting while capturing non-linearities and interactions between predictors. The method allows for modelling the entire conditional distribution, answering questions such as: What factors drive the worst 10% of outcomes in money markets?

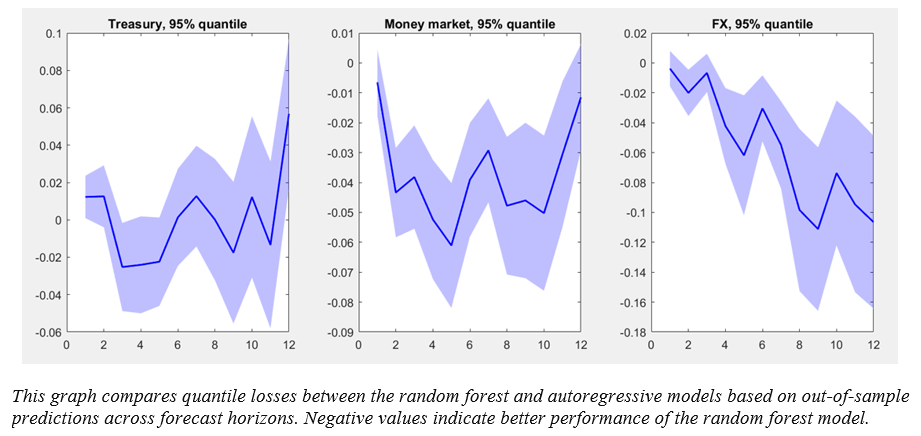

The results are noteworthy: random forest models outperform traditional time-series approaches, particularly in predicting tail risks over longer time horizons (up to 12 months). For example, at the 90th quantile of FX market stress (3-month horizon), the random forest achieves up to 27% lower quantile loss than autoregressive benchmarks (Graph 2).

To address the black-box issue, the study uses Shapley value analysis to explain the main factors driving market stress predictions. Shapley values quantify the marginal contribution of each predictor to a specific forecast, conditional on all possible combinations of other variables. For money markets, current conditions and Federal Reserve Treasury securities purchases emerge as the most important features, along with the global financial cycle indicator and the slope of the yield curve. For FX markets, implied volatility, market sentiment captured by fund flows, and past realisations of the FX and Treasury MCIs stand out. Intra-family fund flows into riskier segments emerge as important predictors of future tail realisations across markets. This reveals that investor overextension in seemingly calm and low-volatility periods often makes markets vulnerable to abrupt shifts in conditions. The relevance of lagged MCI realisations highlights the self-reinforcing nature of illiquidity spirals, while the importance of lagged other markets' MCIs demonstrates the interconnectedness of these markets in the modern market-based financial system.

Combining machine learning with large language models

Aquilina et al. (2025) take a different approach. By combining a novel variant of recurrent neural networks (RNNs) with LLMs, the authors develop a two-stage framework to forecast market stress and identify its underlying drivers. The study focuses on deviations from triangular arbitrage parity (TAP) in the euro-yen currency pair, a key indicator of dysfunction in the foreign exchange market. Such deviations can serve as a 'canary in the coal mine' for broader market dysfunction, since they indicate frictions in one of the world's most liquid markets where arbitrage opportunities should typically be eliminated within seconds. TAP violations are associated with periods of significant market dysfunction and other indicators of strain in global financial markets.

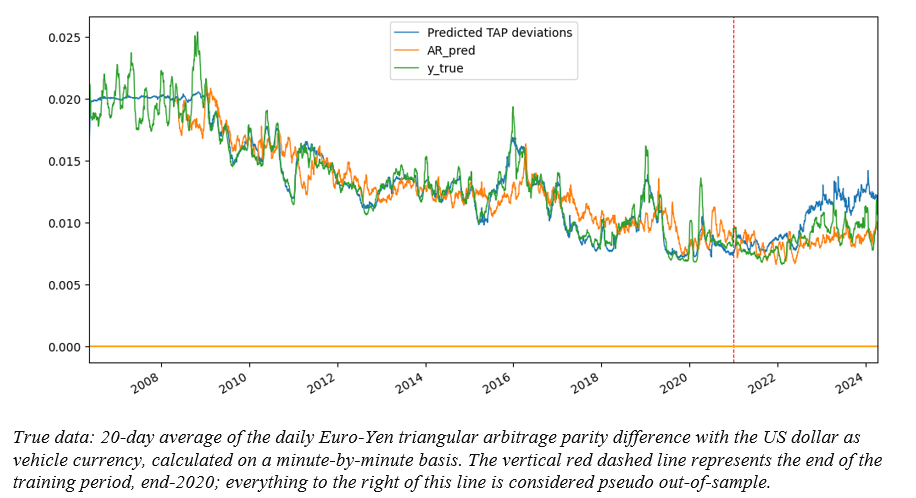

The approach calculates TAP deviations for each one-minute window and uses the daily standard deviation of these minute-by-minute discrepancies as the variable of interest. Using the standard deviation rather than the average ensures the resulting daily series is more sensitive to differences in intraday values and captures deviations in either direction of the trade. Using over one hundred daily financial variables as inputs, including TAP deviations from other currency pairs involving advanced and emerging market economies, bid-ask spreads, equity market volatility, risk reversals, forward FX quotes, and government bond yields, the RNN produces interpretable daily forecasts of market dysfunction 60 business days ahead.

The authors employ Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, a type of RNN that can efficiently model signal from large datasets while flexibly capturing regime-switching behaviour with time-varying dynamics. LSTMs address the vanishing memory problem of early RNNs by adding 'gates' that automatically control the addition of new relevant information, the removal of information no longer relevant, and the retention of long-term concepts useful for prediction. These characteristics are desirable because market liquidity innovations help explain future liquidity, and there is empirical evidence of different persistent regimes in financial markets.

Out-of-sample testing on 3.5 years of data (2021-2024) demonstrates the model's practical value. The RNN model has a particularly useful feature: it is less noisy than both the actual realisations of the target variable and the predictions based on autoregressive models (Graph 3). This implies that when the model is forecasting dysfunction, it is very likely to materialise. For example, the model identified elevated risks before the March 2023 banking turmoil, including signs during the lead-up to the September 2022 LDI event in the UK. This performance occurs even though the model was trained only on data up to end-2020. However, it did not predict the market anomaly caused by the onset of COVID-19, as the event's origins were completely external to the financial system.

To address the black-box challenge, Aquilina et al. (2025) develop a new architecture for recurrent neural network models that dynamically assigns data-driven, time-varying weights to input variables, making its decision process transparent. These weights serve a dual purpose. First, their evolution provides early signals of latent changes in market dynamics. Second, when the network forecasts a higher probability of market dysfunction, these variable-specific weights help identify relevant market variables. The model's ability to maintain a consistent prediction while altering the weights of the predictors is noteworthy, as it predicted market stress in March 2023 by adjusting the weights of different variables despite none of the included variables being directly related to the banking sector where the stress originated.

These weights are then fed into an LLM to search financial news and commentary for contextual information, helping to uncover potential triggers of market stress. To illustrate this technique, the authors used Google's Gemini 2.5 Pro with financial news from July 2023 to forecast the October 2023 'Treasury Tantrum'. The model flagged elevated risks in variables such as USD/CHF risk reversals and AUD/USD forward points. Guided by these signals, the LLM identified news articles discussing diverging views on the Federal Reserve's monetary policy, rapid depreciation of the US dollar hitting a 15-month low against a basket of currencies, and sharp appreciation of emerging market currencies like the Mexican peso, signalling potentially crowded carry trades susceptible to abrupt unwinding. This targeted approach transforms opaque statistical forecasts into narrative explanations that policymakers can understand and act upon.

Conclusions

While much more research into these issues is needed, the analytical work summarised above shows the promise of leveraging AI tools for financial stability monitoring and analysis.

First, the work has shown that machine learning models are useful in forecasting future conditions of various markets. The MCIs serve as real-time diagnostic tools for central banks, flagging market-specific stress that aggregate indices miss. Tree-based models like random forest can capture the non-linear dynamics and complex interactions that drive market stress, achieving significantly lower quantile losses than traditional time-series approaches, particularly at longer horizons. These findings validate ML's role in financial economics, particularly in settings with sparse signals and non-linear dynamics.

Second, the integration of numerical and textual data through machine learning and large language models provides a richer understanding of market dynamics. Policymakers can use these tools to monitor emerging risks in real time, combining quantitative forecasts with qualitative insights from financial news and commentary. LLMs can help supervisors validate and interpret anomalies predicted by ML models, assessing potential causes of future dislocations based on real-time search of financial news.

Third, the interpretability of machine learning models is critical for their adoption in policy settings. Techniques like Shapley value analysis and variable-specific weighting not only improve the transparency of forecasts but also provide actionable information about the drivers of market stress. Shapley values identify systemic vulnerabilities, such as intermediation constraints and crowded trades, that warrant macroprudential oversight. The prominence of variables that capture investor overextension and the global financial cycle underscores the need to monitor non-bank intermediaries and investor leverage cycles, as flagged by recent Financial Stability Reports.

Fourth, both studies highlight the self-reinforcing nature of market stress and the importance of cross-market spillovers. The finding that past MCI realisations predict future stress points to illiquidity spirals, while the relevance of other markets' conditions demonstrates how stress can propagate across the interconnected modern financial system. These insights can help policymakers focus monitoring efforts on key areas and prepare for ex post intervention to prevent more severe consequences.

Overall, these approaches represent a significant step forward in leveraging AI to detect vulnerabilities in financial markets. By combining different methods, the studies offer novel tools for forecasting market stress and understanding its underlying drivers. The work points to several avenues for future exploration. Extending the MCIs to corporate bond and derivatives markets could enhance systemic risk monitoring. Hybrid models combining ML with structural frameworks may improve interpretability further. Incorporating alternative data sources, such as dealer inventories, financing conditions in repo markets, positioning metrics based on granular trade repository information, text-based sentiment, or blockchain-derived liquidity metrics, could refine predictions. However, these methods are not without limitations, such as the risk of overfitting and the need for substantial computational resources. Real-time implementation also requires addressing computational bottlenecks, such as the latency of Shapley value calculations for high-dimensional models. The performance of models can also be improved through wider searches of the parameter space and alternative neural network architectures. It is hence important for policymakers and regulators to keep abreast with investments in the necessary data and infrastructure to fully harness the potential of these tools for safeguarding financial stability.

Note: The article is contributed by Gaston Gelos and Andreas Schrimpf, Bank for International Settlements (BIS) and CEPR. The views expressed here are those of the authors, and not necessarily those of the BIS.

References

Aldasoro, I, P Hördahl and S Zhu (2022), "Under pressure: market conditions and stress", BIS Quarterly Review (19): 31–45.

Aramonte, S, Schrimpf A and H S Shin (2021), “Non-bank financial intermediaries and financial stability”, BIS Working Papers No. 972.

Aldasoro, I, P Hördahl, A Schrimpf and X S Zhu (2025), "Predicting Financial Market Stress with Machine Learning", BIS Working Papers No. 1250.

Aquilina, M, D Araujo, G Gelos, T Park and F Pérez-Cruz (2025), "Harnessing Artificial Intelligence for Monitoring Financial Markets", BIS Working Papers No. 1291.

Du Plessis, E and U Fritsche (2025), "New forecasting methods for an old problem: Predicting 147 years of systemic financial crises", Journal of Forecasting 44 (1): 3-40.

Fouliard, J, M Howell, H Rey and V Stavrakeva (2021), "Answering the queen: Machine learning and financial crises", NBER Working Paper 28302.

Huang, W, A Ranaldo, A Schrimpf and F Somogyi (2025), "Constrained liquidity provision in currency markets", Journal of Financial Economics 167: 104028.

Kelly, B, S Malamud and K Zhou (2024), "The Virtue of Complexity in Return Prediction", Journal of Finance 79: 459-503.

Pasquariello, P (2014), "Financial Market Dislocations", Review of Financial Studies 27(6): 1868–1914.

Shin, H S (2019), “Risk and Liquidity”, Oxford University Press.

Gaston Gelos is Deputy Head of the Monetary and Economic Department and Head of Financial Stability at the Bank for International Settlements. In that role, he is also a member of the Bank’s senior management team. He leads analytical work and oversees the work of the secretariats of various committees, including those of the Markets Committee and the CPMI. He also represents the BIS externally in senior groups, including the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. Previously, he spent 25 years at the International Monetary Fund (IMF), where, among other things, he held positions as Chief of the IMF’s Monetary and Macroprudential Policies Division and Chief of the Global Financial Stability Analysis Division. His research includes work on international finance, financial stability, and monetary policy, and has been published in leading academic journals. He holds a Ph.D. in Economics from Yale University and a Diplom from Bonn University. He is a CEPR Research Fellow.

Andreas Schrimpf is Head of Financial Markets in the Monetary and Economic Department at the BIS. Prior to his current position, he served as Secretary to the Markets Committee (2016-2020). In this context, he coordinated international work in the central bank community on, inter alia, the impact of large central bank balance sheets on market functioning, the FX Triennial Survey and the monitoring of fast-paced electronic markets. Previously, he was a post-doctoral researcher at Aarhus University (2009-11) and a researcher at the Centre for European Economic Research (ZEW) in Mannheim (2005-09). He obtained his doctorate from the University of Tübingen in 2009. His research has focused on the role of intermediaries in financial markets, financial drivers of exchange rates and the intersection of monetary policy and financial markets. Andreas' work is published in leading academic journals, including the Journal of Finance, Review of Financial Studies, Journal of Financial Economics and American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics. He is a CEPR Research Affiliate.