3rd July 2025

Claudio Borio discusses the advantages of using market prices’ cross-sectional information in financial supervision

Key takeaways

- Market prices are much better at reflecting information in the cross-sectional than in the time dimension

- There is a need to increase the reliance on market prices’ cross-sectional information in financial supervision, especially on the information of a more structural nature

Introduction

A perennial issue in financial regulation and supervision is how best to use market price information. The issue is far from straightforward. On the one hand, market prices reflect what may be considered the “best assessment” of the valuation of the assets of an enterprise – a kind of consensus view. The prices aggregate all the information available to market participants, weighed by their willingness to take positions on those assets. Surely, that information must have value. On the other hand, those market prices may exhibit biases – either due to collective behaviour or to the undue influence of a few players. And responding to them may ignite destabilising dynamics, which can precipitate or amplify distress. What, then, is the right balance? And is current practice adequate?

The objective of this short article is to shed light on these issues. The article provides a very high-level analytical perspective on selected challenges in the use of market price information in regulation and supervision, from thirty thousand feet, as it were. The perspective obviously does not answer all the questions; it is simply intended to frame the debate and provide the basis for a more detailed evaluation and prescriptions.

Two takeaways stand out. First, the proper use of market information depends very much on the context and purpose. The key distinction here is between market information as an indicator of how risk, especially system-wide risk, evolves over time– the time dimension – and as an indicator of the relative risk of individual institutions at a point in time – the cross-sectional dimension. Second, regulation and supervision have made more progress in the use of information in the time dimension than in the cross-sectional dimension. Efforts should be stepped up to bridge the gap.

Consider briefly each dimension in turn before drawing some general conclusions.

The time dimension

The Great Financial Crisis (GFC) was a watershed in the predominant perspective for the assessment of risk in the time dimension, especially system-wide risk. The shift was part of the ascendency of the macroprudential perspective of regulation and supervision (eg Borio (2003)). The predominant view pre-GFC saw risk as low in booms/economic upswings and high in busts/downswings. The predominant view post-GFC sees risk as building up in booms/upswings and as materialising in busts/downswings. One can think of the pre-GFC perspective as embodying a kind of “random walk” view of risk, and the post-GFC as embodying a cyclical view. And behind the random-walk view of risk it is easy to see the footprints of market efficiency, which regarded asset price returns – strictly speaking, excess returns – as fundamentally following such a random walk (eg, Fama (1970)).

The key implication of the post-GFC view of risk is that, on balance, market prices should be taken as contrarian indicators of system-wide risk. Buoyant asset prices, compressed credit spreads and low volatility should be taken not as signals of low risk but as signals of high risk-taking. Risk appears lowest precisely when it can be highest. Any use of market prices in macroprudential indicators of risk in the time dimension must take this feature into account (eg Borio and Drehmann (2011)).

This perspective may appear as self-evident now – part of our intellectual furniture. But it was far less embedded in economic thinking at the time. This helps explain why it was not uncommon for supervisors to dismiss concerns about strong credit expansion and buoyant valuations pre-GFC. Personally, I still recall typical statements such as “banks risk management has improved in leaps and bounds since LTCM” or “banks have never been as well capitalised as they are now”. This thinking was deeply embedded in the very foundation of Basel II: the framework took banks’ own risk measurement, which typically relied heavily on market prices as inputs, as the basis for banks’ capital regulation.

The more general point is that markets are much better at assessing and pricing relative risk at a point in time – what arbitrage is all about – than how risk, especially system-wide risk, evolves over time. Tellingly, all the academic literature supportive of market discipline extant pre-GFC was based on assessments of relative risk (eg Flannery (1998)).

Arguably, there are at least three reasons why markets behave this way (Borio (2003), Borio et al (2001)). The first has to do with information. It is harder to assess the evolution of risk over time because it is more difficult to keep “all things equal”. Think, for instance, of the common “uncertainty illusion” – the sense that “uncertainty is especially high now”, which policymakers and markets observers often display, as if there could be a trend increase over time! The second reason has to do with incentives. Think of the pressures to shorten horizons, the standard imperative to keep up with the Joneses and the perception that there is safety in numbers – a common force behind herding behaviour. The third reason has to do with “general equilibrium” effects, ie with the endogeneity of risk. Hence the self-reinforcing mechanisms between financing constraints (funding and market liquidity), asset prices and risk-taking, which are at the core of procyclicality.

Post-GFC, the new perspective on the evolution of risk has been hardwired not just in macroprudential arrangements, but also in microprudential regulation and supervision. The financial cycle and system-wide risk indicators embed this perspective in the macroprudential area, and safeguards against risk weights, such as the leverage ratio or stressed LGDs, dampen the impact of market prices and corresponding risk assessments in its microprudential counterpart.

The cross-sectional dimension

Turning to the cross-sectional dimension raises an obvious question: can more be done to rely on financial market assessments of relative risk? The answer is “Yes”.

Especially promising in this case is what might be termed “structural” information, ie information about the underlying profitability and strength of banks. This type of information is less affected by the ups and downs of financial cycles. And it is less subject to the pitfalls that arise in the mechanical use of market prices in the context of contingent capital or as triggers for resolution. Such a use can give rise to so-called “death spirals”, which can complicate management of stress. In this context, procyclicality raises its ugly head again.

The case of Credit Suisse illustrates the importance of market information. The bank’s capital adequacy metrics looked quite good, but the bank fell victim to a crisis of confidence in a fragile environment, as banks in the United States came under pressure.

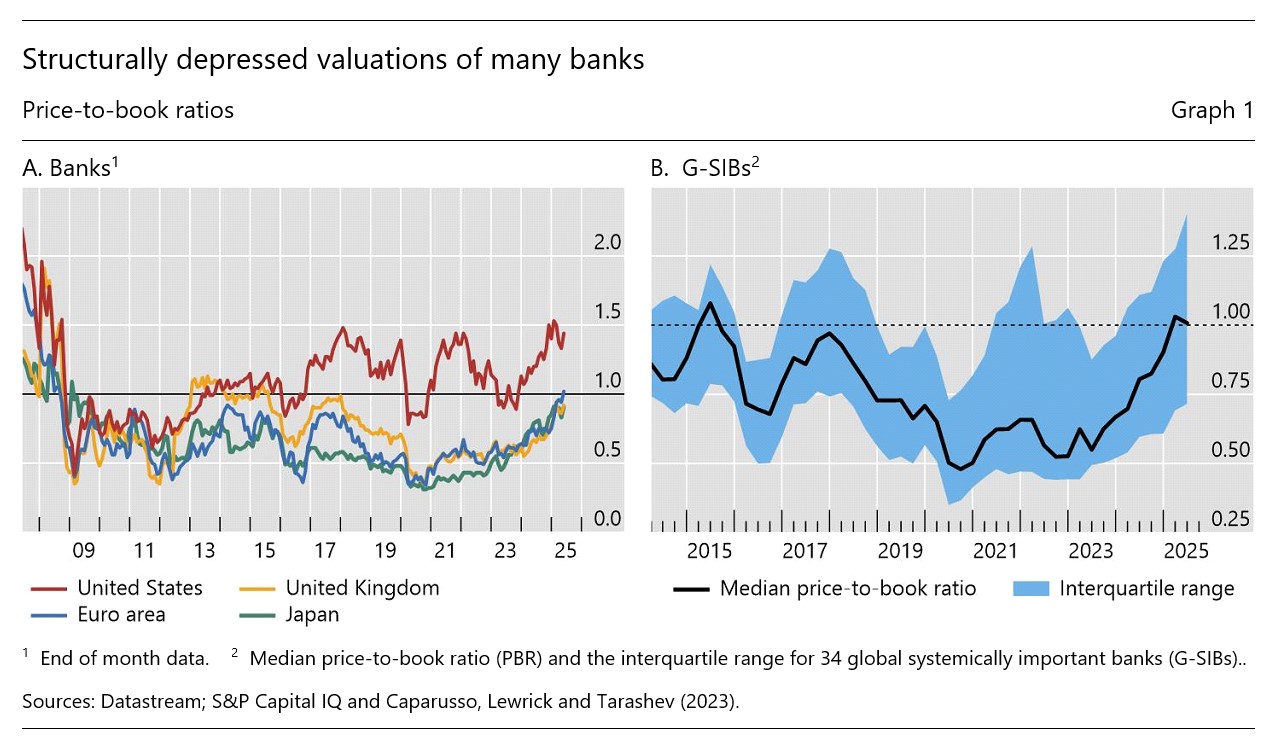

One should take those low price-to-book ratios very seriously. They reflect a mix of concerns about underlying asset valuations and, above all, longer-term profitability (eg, Caparusso, Lewrick and Tarashev (2023)). Profits are the first line of defence against losses. And such low valuations are signal of a structural “exit problem” in banking (Borio (2016)): despite all good work done, in no other industry could some firms continue to stay in the market for so long.

Indeed, the Credit Suisse debacle is the latest reminder of how easily claimants on a bank can switch perspective. They can turn on a dime and switch from accounting metrics to market metrics when assessing banks’ strength. Moreover, the possibility of such a shift is reinforced by contractual terms and risk management practices, such as the common use of triggers in wholesale deposits linked to CDS spreads or equity prices. Things look sustainable until, suddenly, they no longer do.

It is up to supervisors to reflect further on how to incorporate this information in their activities. Many possibilities exist, including as basis for targeting and calibrating intensity of supervision and for addressing some of trickier tasks, such as the adequacy of business models. To be clear, supervisors are already using this information to some extent. But much more can be done.

Conclusion

The GFC marked a kind of Copernican revolution in how economists and those in charge of financial stability regarded the information conveyed by asset prices about risks. While that thinking largely drew on the limitations of the information, we should not lose sight of the corresponding merits. Doing so requires distinguishing clearly between the time- and cross-sectional dimensions of risk. There is substantial scope to exploit the value of that information in the microprudential area, especially in supervision. The opportunity should not be missed.

References

Borio C (2003): “Towards a macroprudential framework for financial supervision and regulation?”, CESifo Economic Studies, vol 49, no 2/2003, pp 181–216. Also available as BIS Working Papers, no 128, February.

Borio, C (2016): “The banking industry: struggling to move on”, Keynote speech at the Fifth EBA Research Workshop on "Competition in banking: implications for financial regulation and supervision", London, 28-29 November 2016

Borio, C and M Drehmann (2011): “Towards an operational framework for financial stability: 'fuzzy' measurement and its consequences”, in R Alfaro (ed), Financial stability, monetary policy and central banking, Santiago de Chile: Central bank of Chile. Also available as BIS Working Papers, no 284.

Borio, C, C Furfine and P Lowe (2001): “Procyclicality of the financial system and financial stability: issues and policy options” in marrying the macro- and microprudential dimensions of financial stability, BIS Papers, no 1, pp 1-57.

Caparusso, J, U Lewrick and N Tarashev (2023): “Profitability, valuation and resilience of global banks - a tight link”, BIS Working Papers, no 1144, November.

Fama (1970): “Efficient capital markets: A review of theory and empirical work”, The Journal of Finance, vol 25(2), pp 383-417.

Flannery, M (1998): “Using market information in prudential bank supervision: a review of the US empirical evidence”, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, part I, August, pp 273-305.

Claudio Borio was Head of the Monetary and Economic Department (MED) from 2013 to the end of 2024. Having joined the BIS in 1987, Mr Borio held various positions in MED, including Deputy Head of MED and Director of Research and Statistics as well as Head of Secretariat for the Committee on the Global Financial System and the Gold and Foreign Exchange Committee (now the Markets Committee).

From 1985 to 1987, he was an economist at the OECD, working in the country studies branch of the Economics and Statistics Department. Prior to that, he was Lecturer and Research Fellow at Brasenose College, Oxford University.

He holds a DPhil and an MPhil in Economics and a BA in Politics, Philosophy and Economics from the same university.

Mr Borio is author of numerous publications in the fields of monetary policy, banking, finance and issues related to financial stability.