28th January 2026

Key Takeaways

- After the Basel III regulatory process-built resistance to shocks by capital and liquidity buffers, there is strong pressure to simplify and lighten the regulatory burden. At this stage, it becomes essential to strengthen the second line of defence. Some useful insight comes from flood control measures once dikes (also known as embankments or levees) suffer some overflow.

- In the end, financial stability does not depend only on frontal resistance but also on its ex post resilience, or its flexible capacity to respond and recover from large shocks (Brunnermeier 2024).

- Resilience needs to be strengthened by a timely response to emerging risks, activating contingent tools aimed at recovery rather than resolution and protected by automatic market stabilizers.

- Credible corrective action needs a clear mandate to intervene upon fewer but more relevant indicators, a mix of supervisory and market signals.

Resilience as a guide for regulatory reform

The Basel III regulatory process has emphasised resistance to shocks, with strong norms to calibrate capital and liquidity buffers, supported by extensive reporting.

While EU banks have weathered well recent shocks, the proliferation of requirements has not always been effective. Costly compliance has taken much managerial attention, often not matched by active enforcement. A massive amount of noisy data is often not actively used. Too many signals add noise to the process, and may provide cover for excessive caution.

Policy attention has shifted to reducing complexity and regulatory burden on banks. This raises the issue of how to maintain financial stability while adjusting requirements.

Can a legitimate simplification drive be complemented by a lighter but more effective supervisory approach?

Financial stability is a combination or frontal resistance (buffers and norms) with contingent resilience (prompt corrective action and recovery). Resistance is the ability to absorb shocks; resilience is the capacity to bounce back from a shock that cannot be fully absorbed. Brunnermeier (2022, 2024) advocates “a shift in mindset beyond static risk management toward resilience management”. 1

The key insight is that stability over time may benefit from less focus on buffers and disclosure and more towards a timely response, activated by fewer but more relevant indicators.

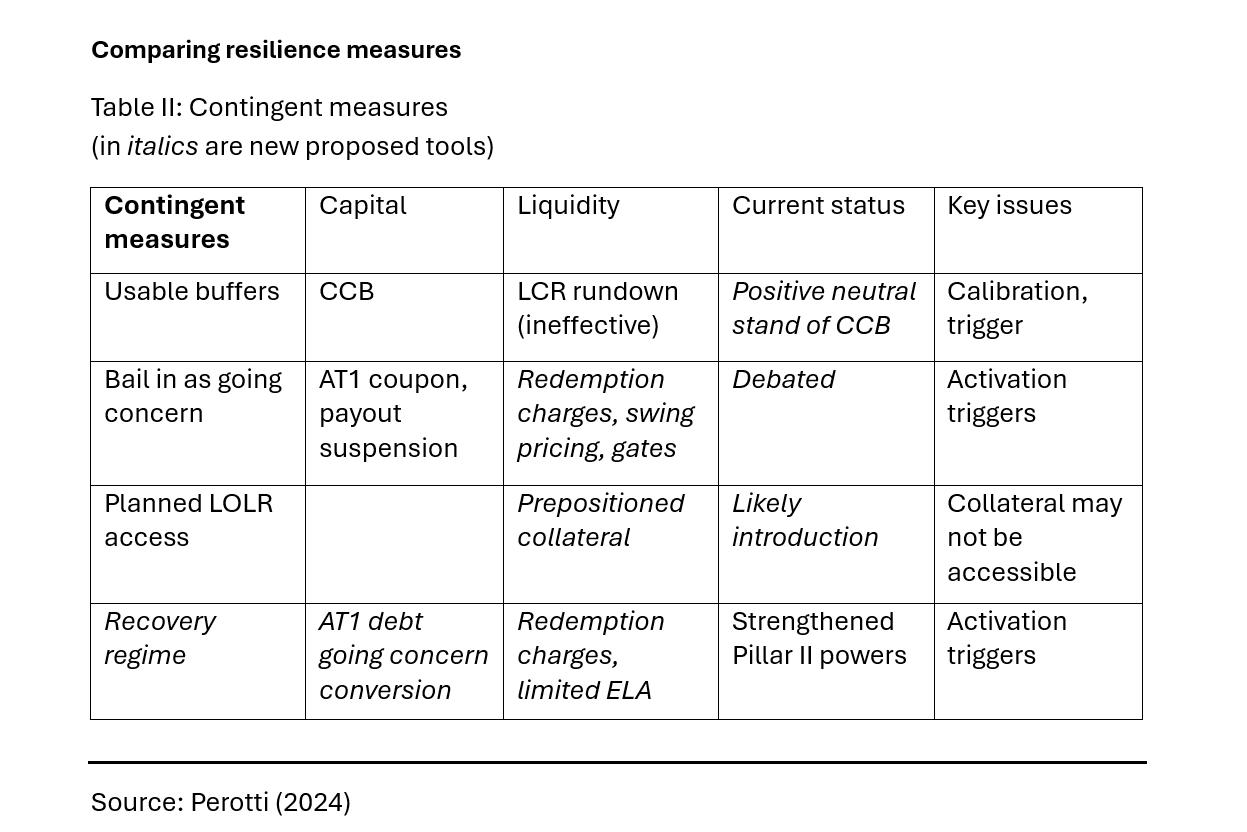

Table I and II offer a classification of tools aimed at frontal solidity (resistance) and contingent resilience. Resistance is provided by the classic capital and liquidity buffers. So far, early containment tools (e.g. usable LCR buffers, AT1 debt conversion) have proven unreliable, as neither supervisors nor banks wish to show any vulnerability, both hoping the trouble may recede.

Resilient response is based on timely activation

A major simplification of requirements may still enable timely bank recovery, if coupled with enhanced supervisory mandate to cope promptly with fewer but more significant indicators as more credible triggers for early intervention. Too many formalistic requirements lead to supervisory hesitation, leading to persistent risk incentives and steady loss of confidence.

To ensure a reliable response it is also necessary to recognize the legal and concrete challenges faced by supervisors. Timely intervention is not credible at present in a context of legitimate concerns about triggering outflows, a situation that will persist unless potential spillover effects are contained.

Arguably, many detailed norms and signals lead to a formalistic approach (tick the box) and excess delay in intervention (Cecchetti and Schoenholz 2023). A focus on fewer but most relevant signals may be necessary to enhance timely response to early signals, and avoids forbearance (Martynova ea, 2022). Next to traditional book values, activation signals should include market signals such as flows (Martino and Perotti 2024) and market prices (Acharya ea 2023).

As market prices are very informative but noisy, they should be used in combination with supervisory assessments. A dual trigger approach allows necessary discretion to filter unnecessary responses when market prices are volatile, while raising the degree of alertness and inducing timely risk assessment.

On the other hand, highly salient signals of potential escalation such as excess outflows should directly activate market stabilizers (circuit breakers), such as automatic redemption charges on uninsured deposit outflows. These would ensure a timely response to disrupt any gradual build-up of self-fulfilling run beliefs. Promptly activated measures can stem escalation of outflows and enhance resilience, just as rapid deployment of sandbags are essential for emergency flood control.

Table 1 provides a simple classification of relevant signals for intervention, outlining their salience, reliability and potential moral hazard.

Challenging the dominant view of runs as unstoppable

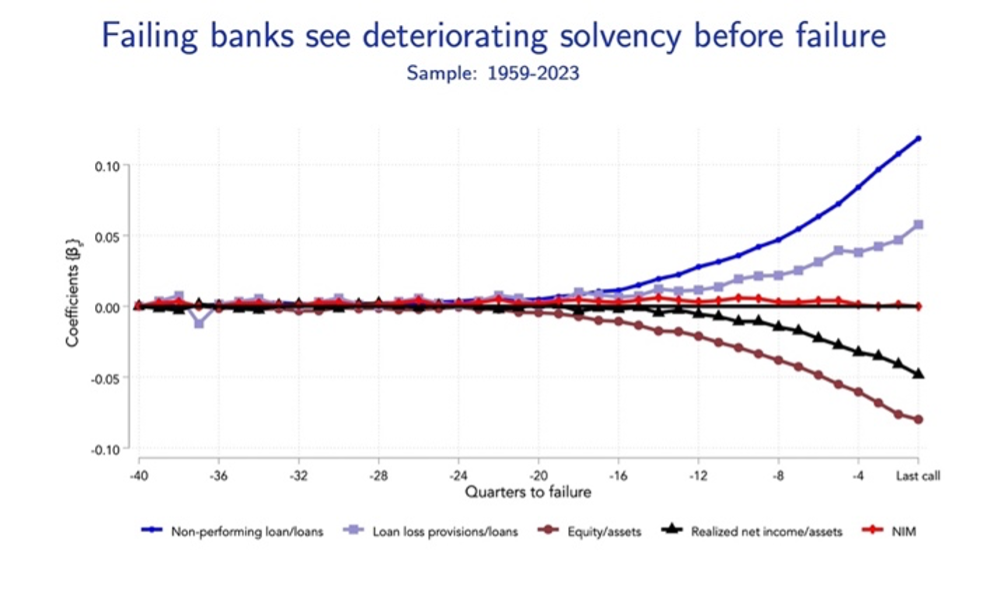

A new approach challenges the view that escalation of outflows into runs is unpredictable and unstoppable. Long term historical evidence on bank failures (Correia, Luck and Verner 2024) offers two insights (see figure 1). First, failures follow after a long phase of progressively deteriorating fundamentals, with bank runs determining the timing of default. Second, failures and runs are highly predictable ahead of time, both on book capital measures (deteriorating solvency) and liquidity risk (increasing reliance on non-core funding).2

Figure 1: Evolution of indicators ahead of bank failures (Correia, Luck and Verner 2024).

A second common misconception is a “black box” view of bank runs, seen as unstoppable once they start. In particular, the conventional view sees early precautionary withdrawals by investors who may need liquidity as inevitably inducing many depositors to withdraw, leading to an unescapable default. In practice there are distinct phases to bank outflows (Perotti 2024), before the key inflection point beyond which the process cannot be stopped.

How can escalation of outflows be controlled?

There is a useful analogy with water overflow over a dike, where flows falling behind the dike wall accelerate and pull water behind it. For depositors who do not need liquidity, there is some incentive to withdraw when the perception that others may withdraw spreads. Thus, de-escalation is essential to resilience.

Reducing withdrawal incentives requires liquidity restrictions, such as imposing gates or redemption charges once outflow pass a certain threshold (on redemption gates, see Matta Perotti 2022). Once automatic stabilizers disrupt the expectation of inevitable escalation and outflows slow down, a key step is to shift the narrative by announcing concrete steps. The key is to disrupt the coordination of beliefs around run risk, and refocus depositor attention on concrete steps to contain risk and support recovery as the new focal point for expectations.

Redemption fees on uninsured deposits, automatically triggered by large outflows would disrupt such expectations. Their immediate effect is to avoid the one-sided incentive to withdraw at par. Even more critically, charges also shift expectations of withdrawals by others, stemming escalation driven by fear of dilution rather than solvency concerns. They may be seen as creating an early “inception point” that disrupts the self-reinforcing effect of outflows by confounding the convergence of beliefs about what others may do.

Redemption fees may be seen as a penalization of avoidable congestion, such as fees penalizing traffic in rush hours. They would not (and indeed, should not) alter the behaviour of depositors with immediate liquidity needs.

Their introduction would have two effects (Matta, Oostdam and Perotti 2024). First, the bank capacity to offer liquidity on demand is enhanced by a lower chance of runs. Second, contingent charges may shift the timing of outflows, when some depositors withdraw earlier in expectation of charges. If these outflows are significant, they will activate charges earlier in time (though not per se more often).

An earlier activation is per se beneficial in a context where response is too often delayed. Trigger a response at an earlier stage when the bank may be still recoverable would have a stabilizing effect (Martino and Perotti 2024).

While imposing charges on uninsured deposits may appear a drastic change, they would align the treatment of cash reserves with new regulation on money market funds (MMF). As these intermediaries have historically served as the primary destination for corporate cash holdings, they represent the closest alternative for uninsured deposits, offering a better yield at the cost of minimal risk. Until last year, money market funds for institutional investors were subject to gates (temporary suspension of redemptions). Since 2023, the new SEC norms require MMF automatic charges, as they maintain access to safe liquidity for businesses.3

Ultimately, charges buy time to define measures aimed at restoring confidence and resolve bank instability, such as a properly negotiated merger.4 Concrete examples the conversion of AT1 debt into equity reducing leverage (Martynova and Perotti 2017), or decisive supervisory interventions in bank governance or its risk profile that refocus investor attention to recovery options. Such concrete measures taken in a timely manner can shift the public narrative on bank prospects.5

Conclusion

Resilience in the face of larger or novel shocks which cannot be fully absorbed requires prompt corrective policy. Some components of a resilient strategy can be preplanned by establishing reserves, such as prepositioned collateral or usable buffers to be activated in going-concern mode (including AT1 debt conversion). A second key ingredient is credibility of timely activation, essential for measures to be effective. Prompt corrective action requires salient activation of resilient tools. A good analogy comes from flood control procedures: bank and dike resilience issues are similar, as they both face shocks that can escalate rapidly if left unattended. In order to empower a resilient supervisory response, a timely intervention mandate needs to be protected from both legal challenges and the threat of runs. Here liquidity restrictions become essential, to discourage panic among those with no immediate need for funding. While both gates and charges can stem outflow escalation, gates are perceived as more extreme and penalize those with authentic liquidity needs.

A new proposed resilience tools is the prepositioning of collateral with central banks for a prompt refinancing response (King 2023), a measure that may be compared to move dam material forward to contain overflow. However, when such preplanned resilience tools prove insufficient, resilience depends on contingent measures. Resolve to act would be much helped by automatic stabilizers of uninsured outflows, such as redemption charges. This would match the new MMF norms, where charges are automatically triggered by rising outflows.6 MMF shares are a functionally equivalent asset class to uninsured deposits; most corporate deposits escaping Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and similar banks in March 2023 went into MMF shares, subject to redemption charges in time of illiquidity.

For a literature review on swing pricing, gates and redemption charges, see Oostdam and Perotti (2025).

Notes

1 A natural analogy for bank resilience comes from dike engineering and flood control measures. While dike height offers calibrated resistance, stability also depends on a prompt response to any breach, and clear procedures to contain overflow and progressive escalation (Perotti, 2024).

2 Interestingly, many defaults come from rapidly growing banks becoming overstretched (Correia ea 2024).

3 Charges are less disruptive than gates, since reliable access to liquidity is more important than absolute safety of principal, as it is the case for corporate deposits.

4 Charge revenues may be segregated to back repayment of unwithdrawn deposits in case of default, further reducing run incentives (Matta Oostdam Perotti 2025).

5Martino and Perotti (2024) propose a short-term recovery regime led by supervisors, activated (and legitimized) by a combination of market and supervisory triggers.

6 The 2020 experience suggests that the activation trigger should be an automatic stabilizer based on salient market signals (outflows) rather than manipulable liquid reserves.

References

Acharya, Viral et al. (2023), “SVB and Beyond: The Banking Stress of 2023”, New York Stern publication

Brunnermeier, Markus (2024), “Presidential Address: MacroFinance and Resilience “, Journal of Finance, Vol LXXIX no 6, December

Brunnermeier, Markus (2022), “The Resilient Society: Lessons from the pandemic for recovering from the next major shock”, Princeton Economics

Carletti Elena, Filippo de Marco, Vaso Ioannidou ad Enrico Sette (2023), “Corporate Runs and Credit Reallocation”, Bocconi University working paper

Cecchetti Stephen and K L Schoenholtz (2023), “Making banking safe”, CEPR Discussion Paper 18302

Cookson, John, C. Fox, J. Gil-Bazo, J. F. Imbet, C. M. Schiller, 2023, “Social Media as a Bank Run Catalyst”, Université Paris-Dauphine Research Paper No. 4422754

Correia Sergio, Stephan Luck and Emil Verner (2024), “Failing Banks”, NBER Working Paper 32907

Martino Edoardo and Enrico Perotti (2024), “Containing runs on viable banks”, CEPR Policy Insight, March; forthcoming in the Journal of Financial Crises, Yale University, 2025

Matta, Rafael, Remo Oostdam and Enrico Perotti (2025), “Containing Bank Runs by Contingent Fees”, Amsterdam Business School working paper, April

Oostdam, Remo and Enrico Perotti (2025), “A literature review on redemption fees”, Amsterdam Business School working paper, March

Perotti, Enrico (2024), “Financial resilience as flood containment”, CEPR Policy insight 136, December; also published as SUERF discussion paper no 1053, December 2024

Enrico Perotti (PhD Finance at MIT, 1990) is Professor of International Finance at the University of Amsterdam. His research has appeared in top journals in economics, finance and law. He has served as senior advisor on financial stability to the DNB board and as member of the ESRB Advisory Scientific Committee at the ECB.

Previously he served as advisor to the EU Commission, the European Central Bank and the Federal Reserve and the Bank of England. He served as Houblon-Normal Fellow at the Bank of England and Duisenberg Fellow at the ECB. His current policy focus are stablecoins and AT1 regulation.

His recent relevant publications and media appearances include: Pay, Stay or Delay? How to Settle a Run (Review of Financial Studies, 2023), Capital forbearance in the bank recovery and resolution game (Journal of Financial Economics (2022), The Swiss authorities enforced a legitimate going concern conversion (VoxEU March 2023), Learning from Silicon Valley Bank’s uninsured deposit run (VoxEU, May 2023), Measures to prevent runs on solvent banks (VoxEU, July 2023).